nodes = 10

node_features_size = 4

adj = torch.empty(nodes, nodes).uniform_(0, 1).bernoulli()Implementing a Graph Neural Network from Scratch

If you are unfamiliar with GNNs in general, please go through my small intro blogpost. Message Passing is one of the more popular concepts in GNNs, and that is what we’ll try to implement here. Specifically we are implementing the Graph Convolutional Layer/Network proposed by Kipf et al in 2016. You can go through a detailed blogpost of his or the original paper.

Representing a Graph

Before we start on to Graph convolutions, let’s first present it out on how do we represent a graph in code. Mathematically, a graph is defined as a tuple of a set of nodes/vertices , and a set of edges/links

. Further, each edge is a pair of two vertices, and represents a connection between them.

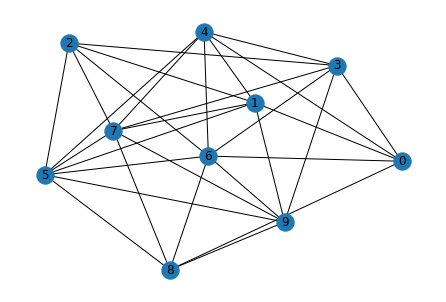

Visually, a graph would look something like this:

The vertices are , and edges

.

There are many ways to represent graphs in memory- two of them include “adjacency matrix” (\(a\)) and “edge list”. If the number of nodes is \(n\), the adjacency matrix is \(n x n\). If there’s an edge from node \(n_i\) to \(n_j\), the element \(a_{ij}\) is equal to 1. Likewise, the other elements of \(a\) are populated.

[[ 0 1 0 0 ]

[ 1 0 1 1 ]

[ 0 1 0 1 ]

[ 0 1 1 0 ]]Working with adjacency matrix for graph operations is easier, although they have their limitations. While established libraries like dgl or pytorch-geometric use edge-list format of data, here we are working with an adjacency matrix.

Graph Convolutions

Graph convolutions are somewhat similar to image convolutions, in that they take their neighbourhood information and aggregate to get a richer understanding of their position. Also, the “parameters” of the filters are shared across the entire image, which is analogous to a graph convolution as well, where the parameters are shared across the graph.

GCNs rely on the message passing paradigm. Each node has a feature vector associated with it. For a given node u, each of its neighbouring nodes \(v_i\) send a message derived from its feature vector to it. All these messages are aggregated alongwith its own feature vector, and this is used to update this node \(u\) to get the final feature vector (or embedding).

Current Implementation

Each node has a feature vector. This feature will be projected using a linear layer, output of which will be the message that each node passes. We will represent the graph as an adjacency matrix, and multiply by the node features (projected) to perform the message passing. This will be divided by the number of neighbours for normalizing, which will give us the output of our first graph convolution layer.

Importing all our libraries. We are not using libraries like dgl or pytorch-geometric, we will be using plain pytorch. We are also using networkx for manipulating graph.

We will be a creating a random matrix as an adjacency matrix. Creating a matrix with uniform_ method and the bernoulli method.

Visualizing the graph we created with networkx library

graph = nx.from_numpy_matrix(adj.numpy())

graph.remove_edges_from(nx.selfloop_edges(graph))

pos = nx.kamada_kawai_layout(graph)

nx.draw(graph, pos, with_labels=True)

Creating random features for our nodes. These features will go through a dense layer and then act as our messages.

node_features = torch.empty(nodes, node_features_size).uniform_(0, 1).bernoulli()#.view(1, nodes, node_features_size)

node_featuresThe features will pass through a linear layer to create our messages

projector = nn.Linear(node_features_size, 5)

node_feat_proj = projector(node_features)

num_neighbours = adj.sum(dim=-1, keepdims=True)

torch.matmul(adj, node_feat_proj)/num_neighbourstensor([[-0.5067, -0.2463, -0.0555, 0.2188, 0.4031],

[-0.8397, 0.0945, 0.5124, 0.1179, -0.0296],

[-0.6457, 0.2369, 0.5048, -0.0216, 0.1531],

[-0.9893, 0.4223, 0.7235, 0.3212, -0.1165],

[-0.5876, 0.2246, 0.5227, -0.1519, 0.1979],

[-0.6133, -0.0359, 0.2532, 0.0760, 0.2250],

[-0.7740, 0.2055, 0.5252, 0.1075, 0.0174],

[-0.7827, 0.1653, 0.5654, 0.0135, -0.0155],

[-0.8635, 0.3189, 0.6940, 0.0758, -0.0423],

[-0.9374, 0.2670, 0.6672, 0.1805, -0.1292]], grad_fn=<DivBackward0>)adj.shape, node_feat_proj.shape(torch.Size([10, 10]), torch.Size([10, 5]))A Note on Above Multiplication Operation

How it does achieve our objective, i.e. summing up of messages from neighbouring nodes of a particular node?

For simplicity, lets take an example where the adj matrix is $ 7 $ and the message matrix is $ 7 $.

Consider a single row from the adjacency matrix, that corresponds to a node \(n_i\). It might look something like \[ A = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1\\ \end{bmatrix} \]

And the message matrix is \(7 \times 5\). (seven rows, five columns).

For this node, we can observe there are edges existent only for nodes \({2, 5, 7}\). When we multiple the above matrix with the message/feature matrix, we will get the elements corresponding to those indexes summed up (since others are multiplied by zero), along the second axis of the feature matrix i.e. we will get a \(1 \times 5\) size vector.

Here, you can see that only the neighbouring nodes’ features have been summed up to get the final d-length vector.

Putting It All Together

Now that we’ve done it step-by-step, let us aggregate the operations together in proper functions.

class GCNLayer(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_feat, out_feat):

super().__init__()

self.projector = nn.Linear(in_feat, out_feat)

def forward(self, node_features, adj):

num_neighbours = adj.sum(dim=-1, keepdims=True)

node_features = torch.relu(self.projector(node_features))

node_features = torch.matmul(adj, node_features)

node_features = node_features / num_neighbours

node_features = torch.relu(node_features)

return node_features

layer1 = GCNLayer(node_features_size, 8)

layer1(node_features, adj).shapetorch.Size([10, 8])layer2 = GCNLayer(8, 2)

layer2(layer1(node_features, adj), adj)tensor([[0.4279, 0.4171],

[0.4724, 0.4304],

[0.4318, 0.3761],

[0.4315, 0.3860],

[0.4520, 0.4132],

[0.4449, 0.4049],

[0.4346, 0.3827],

[0.4614, 0.4176],

[0.4446, 0.3860],

[0.4068, 0.3582]], grad_fn=<ReluBackward0>)class GCNmodel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_feat, hid_feat, out_feat):

super().__init__()

self.gcn_layer1 = GCNLayer(in_feat, hid_feat)

self.gcn_layer2 = GCNLayer(hid_feat, out_feat)

def forward(self, node_features, adj):

h = self.gcn_layer1(node_features, adj)

h = self.gcn_layer2(h, adj)

return h

model = GCNmodel(node_features_size, 12, 2)Solving a Real Problem

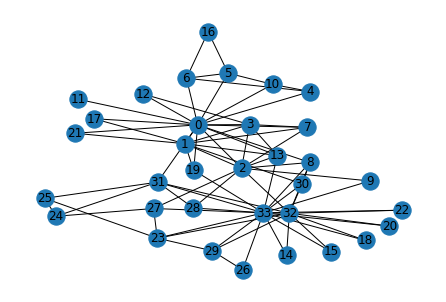

Now that we are able to play around with random data, lets us get to work on some real datasets that we can do basic classification problems on. We will be using the zachary’s karate club dataset, which is a small dataset of 34 people and the edges include their observed interactions with each other. Our objective: predict which group will each of the people go to once their club is bisected.

def build_karate_club_graph():

g = nx.Graph()

edge_list = [(1, 0), (2, 0), (2, 1), (3, 0), (3, 1), (3, 2),

(4, 0), (5, 0), (6, 0), (6, 4), (6, 5), (7, 0), (7, 1),

(7, 2), (7, 3), (8, 0), (8, 2), (9, 2), (10, 0), (10, 4),

(10, 5), (11, 0), (12, 0), (12, 3), (13, 0), (13, 1), (13, 2),

(13, 3), (16, 5), (16, 6), (17, 0), (17, 1), (19, 0), (19, 1),

(21, 0), (21, 1), (25, 23), (25, 24), (27, 2), (27, 23),

(27, 24), (28, 2), (29, 23), (29, 26), (30, 1), (30, 8),

(31, 0), (31, 24), (31, 25), (31, 28), (32, 2), (32, 8),

(32, 14), (32, 15), (32, 18), (32, 20), (32, 22), (32, 23),

(32, 29), (32, 30), (32, 31), (33, 8), (33, 9), (33, 13),

(33, 14), (33, 15), (33, 18), (33, 19), (33, 20), (33, 22),

(33, 23), (33, 26), (33, 27), (33, 28), (33, 29), (33, 30),

(33, 31), (33, 32)]

g.add_edges_from(edge_list)

return g

g = build_karate_club_graph()Visualizing our karate club graph:

pos = nx.kamada_kawai_layout(g)

nx.draw(g, pos, with_labels=True)

We don’t have any node features. So here we’re creating a one-hot vector for each node based on its id. Together, it’d be a single identity matrix for the graph.

At the beginning, only the instructor and president nodes are labelled. Later on each person will join one of the groups headed by these two. So it’s a binary classification, and the only labeled nodes we have are two.

node_features = torch.eye(34)

labeled_nodes = torch.tensor([0, 33]) # only the instructor and the president nodes are labeled

labels = torch.tensor([0, 1])

# since our code only works on adjacency matrix and not on edge-list

adj_matrix = torch.from_numpy(nx.adjacency_matrix(g).todense()).float()

# define our gcn model

model = GCNmodel(34, 32, 2)

# do a single pass just for a check

model(node_features, adj_matrix)Lets get to the meat of it: time to train our model. We create the usual pytorch pipeline. If you’ve worked with pytorch before, this is familiar to you. Even if not, you can get a certain idea if you know some basics of neural networks / backprop.

optimizer = torch.optim.Adam(model.parameters(), lr=0.01)

all_logits = []

for epoch in range(100):

logits = model(node_features, adj_matrix)

# we save the logits for visualization later

all_logits.append(logits.detach())

logp = F.log_softmax(logits, 1)

# we only compute loss for labeled nodes

loss = F.nll_loss(logp[labeled_nodes], labels)

optimizer.zero_grad()

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

print('Epoch %d | Loss: %.4f' % (epoch, loss.item())) Epoch 0 | Loss: 0.6887

Epoch 1 | Loss: 0.6823

Epoch 2 | Loss: 0.6756

Epoch 3 | Loss: 0.6704

Epoch 4 | Loss: 0.6653

Epoch 5 | Loss: 0.6592

Epoch 6 | Loss: 0.6529

Epoch 7 | Loss: 0.6465

Epoch 8 | Loss: 0.6396

Epoch 9 | Loss: 0.6320

Epoch 10 | Loss: 0.6239

Epoch 11 | Loss: 0.6151

Epoch 12 | Loss: 0.6064

Epoch 13 | Loss: 0.5973

Epoch 14 | Loss: 0.5878

Epoch 15 | Loss: 0.5783

Epoch 16 | Loss: 0.5686

Epoch 17 | Loss: 0.5585

Epoch 18 | Loss: 0.5482

Epoch 19 | Loss: 0.5382

Epoch 20 | Loss: 0.5281

Epoch 21 | Loss: 0.5182

Epoch 22 | Loss: 0.5085

Epoch 23 | Loss: 0.4990

Epoch 24 | Loss: 0.4899

Epoch 25 | Loss: 0.4810

Epoch 26 | Loss: 0.4725

Epoch 27 | Loss: 0.4642

Epoch 28 | Loss: 0.4560

Epoch 29 | Loss: 0.4477

Epoch 30 | Loss: 0.4397

Epoch 31 | Loss: 0.4331

Epoch 32 | Loss: 0.4267

Epoch 33 | Loss: 0.4204

Epoch 34 | Loss: 0.4143

Epoch 35 | Loss: 0.4082

Epoch 36 | Loss: 0.4037

Epoch 37 | Loss: 0.3994

Epoch 38 | Loss: 0.3952

Epoch 39 | Loss: 0.3911

Epoch 40 | Loss: 0.3873

Epoch 41 | Loss: 0.3837

Epoch 42 | Loss: 0.3802

Epoch 43 | Loss: 0.3767

Epoch 44 | Loss: 0.3733

Epoch 45 | Loss: 0.3698

Epoch 46 | Loss: 0.3670

Epoch 47 | Loss: 0.3655

Epoch 48 | Loss: 0.3638

Epoch 49 | Loss: 0.3620

Epoch 50 | Loss: 0.3602

Epoch 51 | Loss: 0.3586

Epoch 52 | Loss: 0.3571

Epoch 53 | Loss: 0.3573

Epoch 54 | Loss: 0.3564

Epoch 55 | Loss: 0.3544

Epoch 56 | Loss: 0.3542

Epoch 57 | Loss: 0.3539

Epoch 58 | Loss: 0.3536

Epoch 59 | Loss: 0.3533

Epoch 60 | Loss: 0.3529

Epoch 61 | Loss: 0.3525

Epoch 62 | Loss: 0.3522

Epoch 63 | Loss: 0.3518

Epoch 64 | Loss: 0.3514

Epoch 65 | Loss: 0.3511

Epoch 66 | Loss: 0.3508

Epoch 67 | Loss: 0.3505

Epoch 68 | Loss: 0.3502

Epoch 69 | Loss: 0.3504

Epoch 70 | Loss: 0.3498

Epoch 71 | Loss: 0.3497

Epoch 72 | Loss: 0.3439

Epoch 73 | Loss: 0.3194

Epoch 74 | Loss: 0.2869

Epoch 75 | Loss: 0.2505

Epoch 76 | Loss: 0.2138

Epoch 77 | Loss: 0.1789

Epoch 78 | Loss: 0.1476

Epoch 79 | Loss: 0.1206

Epoch 80 | Loss: 0.0984

Epoch 81 | Loss: 0.0811

Epoch 82 | Loss: 0.0682

Epoch 83 | Loss: 0.0587

Epoch 84 | Loss: 0.0516

Epoch 85 | Loss: 0.0459

Epoch 86 | Loss: 0.0407

Epoch 87 | Loss: 0.0356

Epoch 88 | Loss: 0.0307

Epoch 89 | Loss: 0.0262

Epoch 90 | Loss: 0.0223

Epoch 91 | Loss: 0.0191

Epoch 92 | Loss: 0.0164

Epoch 93 | Loss: 0.0142

Epoch 94 | Loss: 0.0124

Epoch 95 | Loss: 0.0111

Epoch 96 | Loss: 0.0101

Epoch 97 | Loss: 0.0093

Epoch 98 | Loss: 0.0087

Epoch 99 | Loss: 0.0081We can see the loss converging. This dataset doesn’t really have a valid set or anything, so there are no metrics to be presented here. But we can visualize them directly which can be fun to see. Here, we can create an animation of the results of each epoch, and watch them fluctuate as the model converges.

This vis code was taken from dgl documentation. The dgl docs are a great place to start learning about graph neural networks!

import matplotlib.animation as animation

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def draw(i):

cls1color = '#00FFFF'

cls2color = '#FF00FF'

pos = {}

colors = []

for v in range(34):

pos[v] = all_logits[i][v].numpy()

cls = pos[v].argmax()

colors.append(cls1color if cls else cls2color)

ax.cla()

ax.axis('off')

ax.set_title('Epoch: %d' % i)

pos = nx.kamada_kawai_layout(g)

nx.draw_networkx(g.to_undirected(), pos, node_color=colors,

with_labels=True, node_size=300, ax=ax)

fig = plt.figure(dpi=150)

fig.clf()

ax = fig.subplots()

draw(0) # draw the prediction of the first epoch

plt.close()

ani = animation.FuncAnimation(fig, draw, frames=len(all_logits), interval=200)

ani.save("karate.gif", writer="pillow")